SACRAMENTO — Maya Katz-Ali said she never thought she would be able to afford an electric car. She thought it was something unattainable, something for the elite.

And in many ways, Katz-Ali is the opposite of a typical electric-car buyer in California: She’s 26, a woman and a person of color, and she doesn’t earn a six-figure salary. The Oakland native expected to drive her 1992 Volvo until it died.

That all changed last month, when Katz-Ali traded in her car for a new Honda Clarity plug-in electric hybrid with a fraction of the Volvo’s emissions. She bought it with the help of a state subsidy program.

“There’s lots of ideas that you have to be of a certain income bracket to be able to even think about” an electric car, Katz-Ali said. “It’s not just a Tesla thing. It’s not just a higher-class, higher-income thing.”

Electric-car advocates say her initial perception speaks to a diversity problem that the state must solve to reach Gov. Gavin Newsom’s goal of banning the sale of new gas-powered cars starting in 2035.

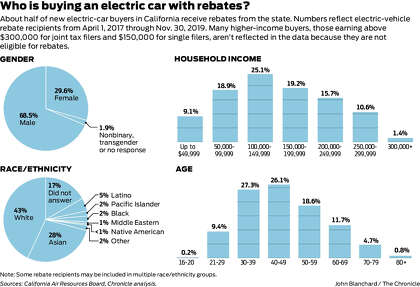

California drivers who buy electric vehicles overwhelmingly fit a narrow demographic profile. Most are male, white or Asian American, and between the ages of 30 and 49. The majority earn more than $100,000 a year and live in expensive coastal areas.

That’s according to data The Chronicle analyzed of buyers who received electric car rebates from the state Air Resources Board, California’s air-quality agency. The rebates, which can total several thousand dollars, are available to people whose income is below a certain level and have not received earlier rebates.

About half of Californians who buy new electric cars receive rebates from the agency, so the data doesn’t include all buyers. However, it is the largest public source of demographic information about electric-car buyers in the state and is a detailed snapshot of the market.

The stereotype of “Silicon Valley dudes buying Teslas” is part perception and part reality, said Lucy McKenzie, a consultant who co-leads the San Francisco chapter of Women of EVs, a group for women who work in the industry.

“There’s widely been a view of electric vehicles as toys for wealthier folks,” she said. “There is a lot of work in California going on to try and highlight that that is not the case.”

Newsom signed an executive order this fall setting the 2035 deadline, the first mandate of its kind in the country. The mandate applies only to new vehicle sales; drivers will still be able to buy and sell used gas cars.

Still, the deadline is ambitious: Only about 6% of new cars sold in the state now are zero emission.

“To get to that (2035) goal, you pretty much have to start getting to everybody who buys cars,” said Ken Kurani, a researcher at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies. “We need to be moving very rapidly. We do need to get out of that narrow band of people.”

Getting there will require the state to dramatically change the demographics of electric-car buyers. The Chronicle’s analysis of rebate data from early 2017 through late 2019 shows the stark disparities:

• Gender: 68% of buyers were men.

• Race and ethnicity: 43% identified as white. The only other racial group to make up a significant portion were Asian Americans, at 28%. Only 5% were Hispanic/Latino, and fewer than 2% were Black.

• Region: Buyers were heavily concentrated in more affluent areas of the Bay Area, Los Angeles and Orange County. The Bay Area’s nine counties are home to slightly less than a fifth of California’s population, but buyers in the region made 32% of electric-car purchases.

• Income: 72% of buyers reported a household income above $100,000, and more than half of those were above $150,000. California had a median household income of $71,228 in 2018.

The wealth gap is probably greater than the data show, because California caps rebates for higher-income earners. People who make more than $150,000 a year, or $300,000 for joint tax filers, cannot qualify for a rebate, except for a hydrogen fuel-cell car.

Policy experts say the disparities are partly due to larger socioeconomic inequities. White men are more likely to buy new cars because they earn more, on average, than women and people of color.

“This matches the demographics for new car purchases overall,” said Lisa Macumber, who oversees the rebate program at the Air Resources Board. “We do recognize more shifting needs to happen.”

Of new-car buyers nationwide, 74% are white and 23% have a household income above $150,000, according to an analysis of Federal Highway Administration data by the Center for Sustainable Energy, a nonprofit firm that helps run the state’s rebate program.

Most electric vehicles also have a higher price tag than gas cars. The best-selling models, the Chevy Bolt and Tesla Model 3, have a starting price of around $37,000, before the state rebates and other financial incentives. New gas-powered sedans typically start at about $20,000.

The higher sticker price of electric cars is a major factor, but it doesn’t alone explain the demographic disparities in ownership, some advocates say. Perhaps the biggest issue is the gender gap.

Women make 45% of all new car purchases in the country, according to Join Women Drivers, an industry group funded by seven large automakers. Yet women buy less than a third of electric cars.

Assemblyman Phil Ting, a San Francisco Democrat and electric-car advocate, said one factor is a narrow range of electric car styles. Most are sedans or sports cars, models that appeal more to single, younger men.

“You have to offer the choices that people want,” Ting said. “The best-selling cars right now are trucks, SUVs and minivans.”

Ting said that will change dramatically in the next 15 years, as more automakers come out with larger electric models. He said the market for used, cheaper electric cars will also grow.

But there are other gender factors at work, advocates say. Amy Sinclair, a consultant in San Rafael who works with electric-vehicle advocacy groups, said a big hurdle for women is range anxiety. She said women are more likely to fear for their safety if they run out of battery power and are stranded.

“It’s a myth, because you can just as easily run out of gas,” said Sinclair, who has owned electric cars since 2011. “I don’t have to stop at a gas station at night.”

Electric-car drivers and advocates say fixing the demographics problem means finding ways to bring the price down and showing that the vehicles don’t require a radical lifestyle shift.

California already has a robust rebate program to get buyers in electric models. The rebates vary depending on the type of car: $2,000 for battery electric, $1,000 for plug-in hybrids and $4,500 for hydrogen fuel cell.

Buyers can receive an extra $2,500 rebate if they are lower income. In addition, the state offers up to a $9,500 grant for people who trade in older, polluting vehicles and buy a new or used electric car.

Katz-Ali, the Oakland native who traded her Volvo for a plug-in hybrid, said she was able to do so only by stacking all the various incentives. She said it made the cost comparable to buying a used, gas-powered sedan.

“I don’t think I ever thought that this would be possible,” she said.

Vanessa Morelan, who runs the clean car grant program at Grid Alternatives Bay Area, a nonprofit, helped walk Katz-Ali through the process. Morelan said a lack of driver education about electric cars is often the biggest deterrent.

She said the state needs to do more to inform people about the fundamentals of electric cars, like how much they save on fuel and maintenance costs and the availability of public charging stations.

“People think that they’re super futuristic, unattainable, a big life switch,” Morelan said. “We really need to target where the buying power is, and that’s within communities of color.”

Many of the nonprofits that help the state award those subsidies target communities of color and non-English-speaking drivers with their advertising and outreach, but activists say it’s only a start.

Another strategy to level inequities in the electric-car market: Stop giving rebates to people who buy luxury models. Last year, the Air Resources Board cut off subsidies for electric cars or plug-in hybrid vehicles that cost more than $60,000.

“You’re trimming out the folks who tend to be freer riders,” said Brett Williams, an adviser at the Center for Sustainable Energy.

But funding for incentive programs is running out. The state’s budget for the current year cut most funding for buyers’ rebates, a move made as California faced a $54 billion deficit due to the coronavirus pandemic. The Air Resources Board has $80 million left in its rebate program.

Macumber, the board’s rebate manager, said the state’s goal is to phase out incentives for higher-income buyers and focus money on helping more diverse people go electric.

“It’s crucial to make sure that the policies we adopt ... are equity-focused,” she said. “The luxury cars sell themselves. We’ve seen that.”

Dustin Gardiner is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: dustin.gardiner@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @dustingardiner

"car" - Google News

November 20, 2020 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/3pUau5p

‘Silicon Valley dudes buying Teslas’: California struggles to expand electric-car market - San Francisco Chronicle

"car" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2SUDZWE

https://ift.tt/3aT1Mvb

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "‘Silicon Valley dudes buying Teslas’: California struggles to expand electric-car market - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment